Using coordinates released by European authorities, a Libyan armed group linked to Wagner and accused of grave abuses illegally pulls back refugees.

Names marked with an asterisk have been changed to protect identities.

A shadowy Libyan armed group accused of unlawful killings, torture, arbitrary detention and enslavement, with alleged links to Russia’s Wagner Group, has been forcibly returning refugees with the help of European authorities, a new investigation has found.

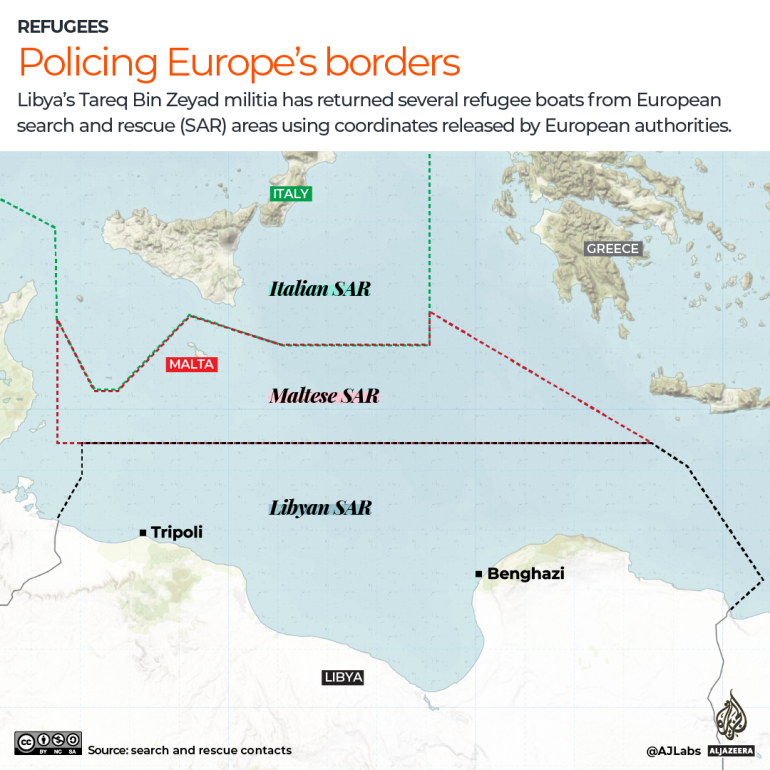

On several occasions this year, GPS coordinates released by Europe’s border agency Frontex have ended up in the hands of the Tareq Bin Zayed (TBZ), allowing militiamen to haul back hundreds of people at a time from European waters to eastern Libya.

The pullbacks described by witnesses, which often involve violence, appear to be illegal. Under international law, refugees cannot be returned to unsafe countries such as Libya, where they are at risk of serious ill-treatment.

The joint investigation by Al Jazeera, Lighthouse Reports, the Syrian Investigative Reporting for Accountability Journalism (SIRAJ), Malta Today, Le Monde, and Der Spiegel, involved months of researching the latest pullbacks, including extensive interviews with witnesses, experts and officials.

The TBZ pullbacks from European waters began in May. Al Jazeera and its partners investigated five that took place this year, which overall saw hundreds being returned and many abused. The TBZ is also known to drag people back from Libyan waters.

The pattern that emerged suggests that European powers are working directly and indirectly with the TBZ, amid their efforts to curb refugee arrivals.

These institutions are well aware of the TBZ’s alleged human rights abuses but do nothing to stop the brigade acting as a coastguard partner, even though it is closely tied to Khalifa Haftar, the renegade general at the helm of the eastern Libyan administration which is not recognised by the international community, including the European Union.

The bloc also understands the TBZ’s connections to Wagner, the Russian mercenary force accused of atrocities from Africa to Ukraine.

The investigation found that Malta appears to be playing a direct role. During one incident in August, an audio recording strongly suggests that a Maltese air force pilot relayed the coordinates of a boat in distress to the TBZ.

Several refugees who have been intercepted by the group told Al Jazeera and its partners that TBZ militiamen have tortured, beat, and shot at them. One said they witnessed a killing. Others, having paid vast sums to smugglers, said TBZ forced them to pay ransom or made them work for their freedom.

“Frontex and national rescue coordination centres should never provide information to any Libyan actors,” said Nora Markard, an expert on international law at Germany’s University of Munster. “Frontex knows who TBZ is and what this militia does.

“What the militia is doing is more of a kidnapping than a rescue. You only have to imagine pirates announcing that they will deal with a distress case.”

‘They beat us’

In late July, Bilal*, a 23-year-old Syrian, and more than 250 others from his war-torn country, Egypt, Pakistan and Bangladesh boarded a boat in Libya under the cover of night. Most paid thousands of dollars to smugglers for the journey, which they hoped would lead to a safer and more stable living in Europe.

“We were stacked on top of each other inside the naval vessel, with barely a centimetre between us,” he said.

As they sailed across the Mediterranean, conditions were harshest for those packed on the lower deck, including women and children.

Some fainted after inhaling fumes of the petrol-powered engines. Others “almost suffocated”, said Bilal. Refugees prayed for land.

On the morning of July 26, two days after departing eastern Libya, Frontex issued a mayday call when the boat was still in Libya’s rescue zone, close to Maltese waters.

“The vessel was far away from the shoreline, it was overcrowded, and there was no life-saving equipment visible,” the agency told Al Jazeera.

But neither official Libyan nor Maltese authorities, which are obliged to lead search and rescue operations in their areas of responsibility, acted on the call. Maritime imagery also shows that two commercial vessels sailing in the vicinity did not change course.

Instead, it was the TBZ, with its large blue and white vessel, that heeded the mayday and sailed towards Europe.

Seven hours later, militiamen boarded the boat, which was now within Malta’s rescue zone. Later, they instructed the refugees to move onto their TBZ ship.

Waves were high, making the transfer treacherous.

“Jumping between the ships was extremely dangerous,” Bilal said.

The TBZ eventually boat docked at the port of Juliana, in Benghazi.

“Severe beating and violence ensued,” Bilal said. “[TBZ militiamen] confiscated our passports and mobile phones and transferred us to a prison within the port, a large hangar about 50 metres long, already crowded with about 600 people.”

Syrians were spared the worst treatment, which seemed to be reserved for Pakistanis and Bangladeshis who, Bilal said, faced “brutal” abuse.

Bilal and his countrymen were released after two days, while refugees of other nationalities remained in arbitrary detention.

“They [let us] leave, but when we asked for our phones and passports, they beat us with hoses,” he said.

Torture, abuse, slavery

Seven witnesses interviewed by Al Jazeera and its partners said they suffered violent abuse at the hands of the TBZ.

In the most appalling example recounted by a Syrian teenager, the militia allegedly killed an Egyptian refugee who was unable to answer their questions and dumped his body overboard.

A militiaman involved in the May pullback had asked passengers to identify the captain, the Syrian refugee remembered.

The Egyptian refugee in question “replied that he did not know, so the soldier shot and killed him, then threw him into the sea”, the Syrian teenager said.

At the time of publishing, the TBZ had not responded to requests for comment.

Other refugees described acts of intimidation, saying the TBZ had fired water cannon or shot at them.

Several said food was another way of punishment; often in detention, there was just one meal a day such as rice cooked in seawater, or a slice of bread.

Bassel*, a 36-year-old Syrian who was pulled back on August 18, said militiamen used ropes to stop their boat from progressing towards Italy.

“The officers entered our boat with weapons … and they beat the men with sticks,” he said.

Once they arrived in eastern Libya, the TBZ fighters shaved their heads and eyebrows.

“We received severe beatings to the point that our bodies turned black,” said Bassel.

One of the militiamen “hit me hard on the head … I felt like my head broke”.

After beatings, they would throw their victims in the sea, so that sea salt rubbed into wounds.

Bassel remembered being allowed to sleep by the toilet, on a floor covered in excrement and blood.

“At 6:30 in the morning, they beat us again,” he said. “They took our money … They threw our papers and documents in the [sea].

“They also harassed and assaulted the women.”

Bassel counted 22 days of torture. Like others, he was later enslaved because he did not have any money to pay for his freedom. Yet again, he was taunted by the TBZ and threatened with execution.

Other survivors reported paying up to $1,000 in ransom.

Some were threatened with guns.

Another Syrian said he was “sold to businessmen to work for free” for several days after his boat was intercepted in July. A TBZ fighter supervised the construction work, shouting and throwing insults.

“We understood that what this brigade is doing to us is not allowed,” said the Syrian man. “It is slavery.”

Al Jazeera was unable to independently verify all of the refugees’ allegations, but the accusations are consistent with previous reports.

Last year, Amnesty International documented serious violations by the TBZ, which is led by Saddam Haftar, Khalifa’s son, and operates under the umbrella of the Libyan National Army (LNA).

Libya is split between warring administrations in the east and west. The self-styled “national” army holds sway in the Haftar-controlled east, a rival faction to the Western-backed Government of National Accord (GNA) based in Tripoli.

Amnesty reported on TBZ acts of torture, sexual violence, unlawful deprivation of liberty and murder. It also found the militia guilty of expelling refugees en masse from Libya to neighbouring Niger, denying them an opportunity to seek asylum.

On social media accounts reviewed by Al Jazeera, the TBZ paints itself as a fearsome force.

In one slickly produced video, men wearing balaclavas are seen showing off machine guns as the rap song “Get low” plays in the background. On TikTok and Instagram, some posts show them posing in designer clothes, while they are seen relaxing in others, tending to barbecues on the vessel they use to intercept refugees.

According to a United Nations report published in September, the TBZ is financed by “fuel smuggling, migrant smuggling, trafficking in persons, and drug trafficking.”.

The brigade receives funding and military equipment from the LNA, some of which appears to have originated from the United Arab Emirates and Jordan, the report said. Some TBZ fighters have received military training in Jordan, it added.

According to its registration documents, the TBZ vessel belongs to a company named 2020 Volume Boat Maintenance, registered in the UAE.

The company did not respond to requests for comment.

Wagner connections

The EU and recognised Libyan authorities have worked together on migration for years.

In June 2018, the European Commission financed the creation of a Libyan search and rescue (SAR) zone, providing authorities in the UN-recognised government based in Tripoli with surveillance assets and a trained coastguard.

But two years later, UN experts found that refugees being returned to western Libya faced unlawful detention, “sexual slavery”, and other abuses.

In March, the UN called on the EU to suspend all support to Libyan “actors” involved in “crimes against humanity” against migrants and refugees.

Rather than complying, European authorities appear to be allowing collaboration to develop with the eastern Libyan government, which they do not formally recognise, and the affiliated TBZ brigade.

European institutions seem to be aware of the ongoing pullbacks, TBZ’s track record, and its connections to Wagner, according to documents seen by Al Jazeera and its partners.

A report from the European External Action Service (EEAS) stated the TBZ was known to be “supported” by Sudanese mercenaries and the Wagner Group, the Russian state-funded private military.

Wagner, a proscribed terrorist group under EU legislation, was blacklisted by the bloc in 2021.

European Commission spokesperson Peter Stano said the EU does not regard the TBZ as an “appropriate” partner, but added that unlike Wagner, the eastern Libyan group has not been designated as a “terrorist” organisation.

The Russian group shares military bases with the TBZ in Libya, but does not play a role in the “migration business” yet, according to Wolfram Lacher, Libya expert and political scientist at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs.

“Saddam Haftar is the most important player in eastern Libya today, more important than Khalifa [Haftar],” he said. “The TBZ is the most important unit and Wagner is the most important partner.”

Internal documents also reveal European attempts to normalise collaboration with the armed group.

An incident report compiled by Frontex refers to the TBZ vessel as “Libyan coastguard” and confirms that the agency is aware that GPS coordinates of refugee boats in distress end up with the militia.

Bassam al-Kantar, Libya researcher for Amnesty International, said the TBZ should not be considered part of the coastguard because it has “terrorised” people since its emergence in 2016.

Amnesty is among the groups that have called on the EU to stop cooperating with Libya on migration and border control.

“The international community, including the EU, needs to change its approach to Libya and prioritise human rights over short-sighted political interests. Without concrete measures to rein in Tareq Bin Zeyad and hold it accountable, countless others are at the mercy of [the armed group],” al-Kantar said.

For its part, Frontex told Al Jazeera and its partners that it is “committed to working closely with rescue coordination centres and other relevant authorities to save lives at sea”.

It claimed that decisions on how to proceed with a rescue operation, including the choice of vessels to be deployed, “are made solely by these coordination centres”.

But referencing the July 26 incident, legal expert Markard said Frontex should have made sure its mayday did not lead to a dangerous pullback.

“Frontex officials know that people in Libya are at risk of torture and other inhumane treatment,” she said. “The agency should therefore have ensured that someone else took over the rescue after the distress call – for example, one of the merchant ships, which would have been on site much faster anyway.”

German NGO Sea-Watch, which operates rescue missions, said its vessels are never informed by Frontex of refugee boat locations, and very rarely by coastal states. As a result, the TBZ and Libyan coastguard assets are often the first to intervene, despite being several hours away.

Sea-Watch filed a lawsuit against Frontex last year in an effort to obtain documents it says prove that the agency is involved in human rights violations.

“Frontex systematically uses secrecy to evade accountability,” said Sea-Watch spokesperson Felix Weiss.

‘I have a position for you’

The normalisation of the eastern Libyan militia is most apparent in Italy and Malta, two countries which have expressed a deep desire to repel refugees.

Refugee arrivals to Italy from eastern Libya in the first half of 2023 surpassed those from western Libya, rising almost sixfold compared with the same period last year.

As the TBZ began intercepting boats this year, Italian and Maltese officials travelled to Benghazi to meet Haftar.

“You can’t deal with Libya, as a whole, without talking to him,” a high-ranking Maltese official who requested anonymity said of Haftar.

In an audio clip recorded on August 2 at 05:45 GMT, a pilot can be heard directly contacting the TBZ.

“I have a position for you,” the male voice said, before relaying a series of numbers to the brigade.

A few hours later, the TBZ was seen pulling refugees back from Maltese waters.

It was not possible to establish if the aircraft belonged to Malta’s air force, but analysis strongly suggests the coordinates were shared by a Maltese officer.

Two linguists who examined the recording found it to be compatible with a Maltese accent.

Maltese authorities did not deny or admit to collaborating with the TBZ on the August incident or other interceptions in Maltese waters.

The Armed Forces of Malta said it was “common practice” for “all mariners” to share information with vessels in a certain area to assist a boat in distress.

“One might call it pushback by proxy, with TBZ acting on behalf of Malta,” Markard said. “This is a very clear violation of the law of the sea.”

Source : Al Jazeera

Add Comment